THREADS OF SUCCESS

- 06 Apr - 12 Apr, 2024

A one-man show was held each month, exclusively for the neighbourhood kids, but each time the solo performer's act would bring out a unique character, as he performed in light shed off by a lantern, in front of a white curtain; he would either drape a sari and play the housewife or don a sherwani and act out a grandfather's role. Lasting about an hour, he would charge four anas for the play with kids raging for more... only to receive more of the young thespian’s act a month later.

Name him, and you need no introduction. An institution in himself, one that has a class of its own, Anwar Maqsood is a "die-hard human being", he colours his self-drawing with words. Making a quick exit each time at school, Maqsood was "a very bad student". "I would try to run away from the class and would especially miss the Math class," recollects the multitalented virtuoso who would end up befriending his Math teachers. "I would question the teacher how algebra or geometry would help me on the Day of Judgement?" Maqsood shares. But he would always clear his examinations without cheating. "I always passed in the second division," says the master pensmith who "always got the first prize in debate and spent a lot of time painting in class."

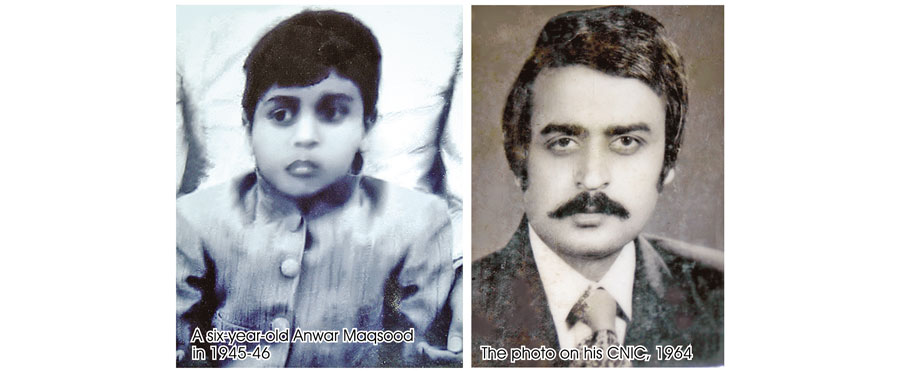

With the emergence of Pakistan on the world map, Maqsood and his family migrated to the newly born country in 1948. "Till the third grade I studied in Hyderabad Deccan, India, but after coming to Pakistan, I attended a school on jail road, called Bahadur Yar Jung High School," says the student of Khawaja Moinuddin, who has penned plays like Taleem-e-Balighan and Mirza Ghalib Bandar Road Par.

Maqsood's family wanted him to pursue science and so, he was accompanied by his maternal uncle to D.J. Sindh Government Science College. "From there I took a bus to Nazimabad and enrolled myself in Arts at the Government College, for I couldn't study science," he sheds light on his school days.

After graduation, Maqsood soon started working. "I was a very bad employee," he quips, but was equally fond of music, painting and acting, and plays are what he did with his former classmates. "I was the magazine editor of Hurriyat; but was made to leave after I had written an editorial against General Ziaul haq," Maqsood states.

Soon after, he found a place, "his kind of place" as he likes to call it, where he enjoyed working, "EMI was where I worked for long," shares the artist who had music maestros visiting his home off and on."Ghulam Farid Sabri, Fareeda Khanum and many others used to come at my place," says the musician who has his own library of classical music which includes "Wilayat Khan Sahab's 600 hours of sitar recordings, a complete collection of Roshan Ara begum's songs, as well as The Beatles, Simon Garfunkel, The Beach Boys, Beethoven, Mozart," says the music collector who has a reservoir of global music.

It was in September 1948 that his family moved to a ‘dream’. "We left a lot in Hindustan," he shares. "My nana was a commissioner in Hyderabad Deccan, and a student of Daagh Dehlvi. We had mushairas regularly, and Abul Ala Maududi and Maulvi Abdul Haq were frequent visitors at my nana's house," Maqsood talks about growing up in a literary household. "My nana had a huge library with almost about 20,000 books. So when we migrated to Pakistan, we only brought books with us," he narrates.

Once in Karachi, there were houses that were vacant. "We were told by the government to move in any of the houses, but we didn't," as the high moral codes of the family intervened. "Instead, we bought a piece of land on Jamshed Road and bought tents from Nizamuddin Sons and lived in those tents only. Once PIB colony started developing, we moved there," he brings to mind the early days spent in the newly born state.

"Karachi back then was a dream, unlike a nightmare which it has now turned into. The megacity that it has become, Karachi is the mother of Pakistan who welcomes everyone with open arms," Maqsood articulates how "the Khyber Mail has been coming to Karachi since 1948, and is always packed with people, but those who get dropped here do not return, and like a mother not willing to let go of her children, Karachi, too accommodates all those who decide to reside here."

When Maqsood came to the City of Lights, there was just one medium of communication - radio. "There was one theatre near Empress Market, the Katrak Hall, which was owned by Parsis. Soon after, another one was built near Bunder Road (now M.A. Jinnah Road), called Theosophical Hall," he paints a young Karachi with memories. "There were shops that would sell 78 RPM records which one could get for Rs. 1 and 20 paisas," a glimpse of fondness of those days is evident on his facade. "People would go to Keamari, Manora in boats or visit the Clifton beach. There were six-seven picture houses, Nishat, Naz, Ritz, Mayfair, Rose Palace, and two-three hotels, Beach Luxury and Palace, but people were happy," and happiness flew in content. "The house we lived in, in PIB Colony for nine years had no electricity, no fridge and no car, but there was no sense of deprivation amongst us even though we left behind so much in Hindustan," he points out that problems arise when there are demands. "In the two-bedroom quarter the 10 of us siblings resided along with amma, abba, nana, nani and our great-grandmother," he talks about how a sense of togetherness and gratitude soared.

It was within, and through these walls of the Maqsood household that art and music thrived. "(Fatima Surraiya) Bajia started writing when she was 12, and that was when she wrote her first novel, Muslim Samaj; Zehra (Nigah) apa started shairi at the age of 14, and a year after she went to India for a mushaira," and it was then as Maqsood shares, that he started painting.

"Sadequain Sahib and Shakir Ali Sahib would come at our place and I used to draw on the wall with coal. One day Shakir Sahib enquired who makes these drawings and after he found out it was me, he asked me to fill in colour. When I told him I didn’t have any, he got colours for me," Maqsood lights up, as he shares a memory with the grand masters.

Having many feathers to his hat, Maqsood points out, he was inclined more towards painting. "Painting was my main (craft) but when I saw Bajia writing serials, Zehra apa pursuing serious shairi, Sarah (Naqvi) apa working in broadcast, it was then that I ventured into satire, jo sab say mushkil kaam hai," which Maqsood was working on since his school days. "I loved reading books, used to watch films; Madhubala sey mujhy ishq hogaya tha and I used to watch every film of hers," and it was then that his interest developed for English music.

With some great names penning satire, the likes of which include Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi, Zareef Jabalpuri, Majeed Lahori, Ibrahim Jalees, Khawaja Moinuddin, who was also Maqsood's teacher, there were a few who were skilled at this form of writing. "But I used to write about the issues at hand," he points out. The wordsmith who has produced plays like Sitara Aur Mehrunissa, Aangan Terha, Fifty Fifty, Show Sha, Studio Dhaai, Show Time, Silver Jubilee, Studio Ponay Teen, to name a few, is gloomy on the kind of TV serials that are aired today.

This face of the nation has received three awards, all of which were honoured upon him during democracy. “Hilal-e-Imtiaz, the biggest civilian award, was given to me during democracy; Pride of Performance was awarded to me by the Late Benazir Bhutto; Quaid-e-Azam Gold Medal, too I received in a democratic regime,” states the satirist.

He is one who does not go for designer wear and imparts where he shops from. “Zainab market is where I shop from. Be it any party, I wear khussa and do not wear suits,” shares the artist who spends his evenings with friends which include poets, writers, and as sundown approaches, the talks take over the course of discussions.

Talking about stars of the entertainment industry, the playwright’s tone is dismal. “Visit houses of people who work in the entertainment industry and you won’t find books there; instead you will come across golden sofas, air conditioners, similar sets of vases and lamps, but kitab aik bhi nai hahi. They don’t get the daily newspaper at home,” he laments how “people get fame here quickly but to maintain the stardom, they have to cross a fiery river in order to keep their name going and to maintain that, one has to strive and struggle very much.”

Seeing the bout of films that are being released quite regularly, Maqsood declares the stories are weak. “If the story is good, people will watch it even if the director and performers are not good, but here what I see is that there is no storyline. Unfortunately when I watch (a film), I get a seat next to the filmmaker so I cannot even walk out of it, instead have to watch the complete film,” he makes it known.

The dramatist had not written for stage in 50 years. It was when Dawar Mehmood and his boys came to Maqsood’s doorstep and convinced him to pen a script for them, did he write Sawa 14 August for them followed by Aangan Terha, Ponay 14 August, Dharna and Siachen.

Starting his day at six in the morning, Maqsood listens to music followed by reading the daily paper, a regimen he has been following for years. The script writer of Loose Talk, one of the greatest comedy shows ever, spills how he would pen the script for the show. “Each morning I would pick a news and the entire show would be based on it.” The sync he shared with the Late Moin Akhtar was unmatched and showed evidently on screen. “Whatever I used to write, Moin would follow without even a cough; if for instance the script read ‘Moin yahan tang meiz par rakhey ga, yahan ainak utar kar phekay ga’ he would do exactly that; everything was scripted, and the show completed 397 episodes with no set, just two chairs, a table and a new script every time, aur yeh Moin ka hi kamaal tha,” shares Akhtar’s best aide who wrote for him for 38 years.

Now, Maqsood is penning theatre for his own self. “Kyun will be staged in December 2017. It is based on girls who work and come home late from work, and their parents worry about their whereabouts. They can be late because they may not be able to find transport and not every girl has a mobile phone. Distrusting and suspecting girls who work hard is the worst thing one can do.” Another project of his which will be aired weekly is Mismanagement that will hit the screens in February 2018.

If anyone can play the role of Anwar Maqsood, it is “Khawaja Saad Rafique”. Responding spontaneously, I enquire has this frame of thought crossed his mind? “Har chez hi karlytay hain woh,” up front comes the reply from the individual who houses a museum of wit within himself. •

COMMENTS