12.4 Anatomy of the Digestive System

Digestion (dī-JĔS-tĭon) is the process by which food is broken down into absorbable units. This section will provide an overview of the anatomy of the digestive system, including the mouth, tongue, salivary glands, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, as well as the accessory organs of the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. See Figure 12.1[1] for an illustration of digestive system organs.

![]"abe85277d60c52f85be133e1b5ddc40aea009e1c.jpg" by J. Gordon Betts, et al. is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system. Illustration showing human digestive system with labels for major parts](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/46/2023/05/abe85277d60c52f85be133e1b5ddc40aea009e1c-824x1024.jpg)

The peritoneum (pĕr-ĭ-tō-NĒ-ŭm) is the serous membrane lining the cavity of the abdomen and covering the abdominal organs. Peritonitis (per-ĭt-ŏ-NĪT-ĭs) refers to inflammation of the peritoneum. Read more about peritonitis in the “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System” section.

Mouth

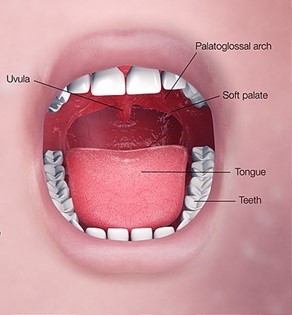

The mouth, cheeks, tongue, and palate form the oral cavity (ŌR-ăl KAV-ĭ-tē). See Figure 12.2[2] for an illustration of the oral cavity. If you run your tongue along the roof of your mouth, you’ll notice the roof of the mouth has an arch called a hard palate (HARD PAL-āt). The anterior region of the palate serves as a septum (i.e., wall) between the oral and nasal cavities, as well as a rigid shelf against which the tongue can push food when swallowing. The hard palate ends in the posterior oral cavity where the tissue becomes fleshier. This part of the palate, known as the soft palate (SOFT PAL-āt), is composed mainly of skeletal muscle that can be manipulated for actions like swallowing or singing.[3]

A fleshy extension of tissue called the uvula (YŪ-vyū-lă) drops down from the center of the soft palate. When swallowing, the soft palate and uvula move upward, helping to keep foods and liquid from entering the nasal cavity and respiratory tract.[4]

Two muscular folds extend downward from the soft palate on either side of the uvula. Between these two folds are the palatine tonsils, clusters of lymphoid tissue involved in the immune system. The lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue.[5]

Stomatitis (stō-mă-TĪT-ĭs) refers to inflammation of the mouth. Xerostomia (zēr-ŏ-STŌ-mē-ă) refers to the condition of a dry mouth. Uvulitis (ū-vyŭ-LĪT-ĭs) refers to inflammation of the uvula. Gingivitis (jin-jĭ-VĪT-ĭs) refers to inflammation of the gums.

Tongue

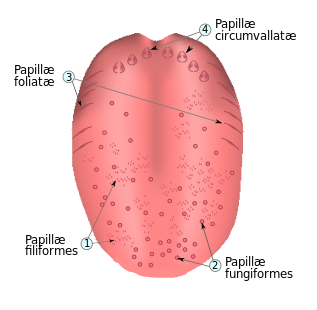

The tongue (TUNG) facilitates ingestion, digestion, sensation (of taste, texture, and temperature of food), swallowing, and vocalization. It has a mucous membrane covering and is composed of skeletal muscles that facilitate eating, swallowing, and speaking. The top and sides of the tongue are studded with papillae and taste buds to facilitate sensation. Lingual glands secrete mucus and a watery fluid that contains the enzyme lipase, which becomes active in the acidic environment of the stomach.[6] See Figure 12.3[7] for an illustration of the tongue and its papillae.

Glossitis (glo-SĪT-ĭs) refers to inflammation of the tongue. Sublingual (sŭb-LING-gwăl) means “pertaining to under the tongue” and is also a route of medication administration.

Salivary Glands

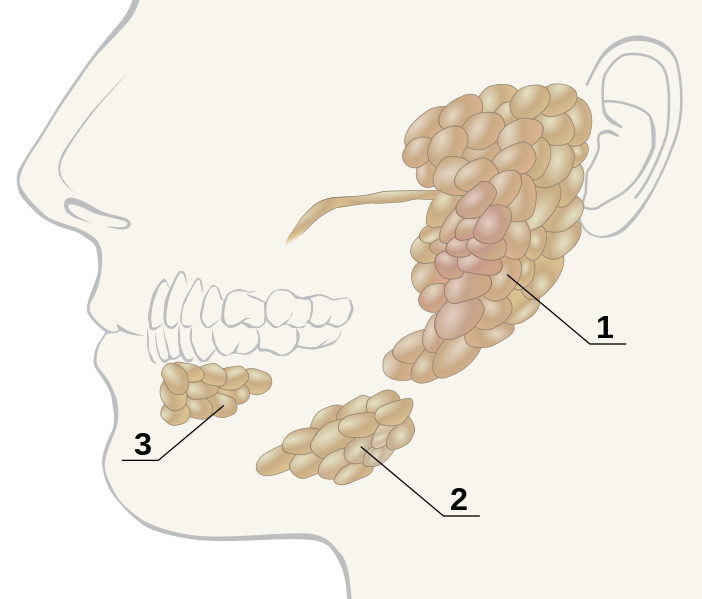

Salivary (SĂL-ĭ-văr-ē) glands are housed within the mucous membranes of the mouth and are constantly secreting saliva into the oral cavity to keep the mouth moist. Saliva secretion increases when eating or even thinking about eating food. Saliva contains an enzyme called salivary amylase, which starts the breakdown of carbohydrates in the mouth. There are six salivary glands that secrete into the oral cavity – two parotid glands located in the cheeks anterior to the ears, two sublingual salivary glands located beneath the tongue, and two submandibular salivary glands located just beneath the mandible.[8] See Figure 12.4[9] for an illustration of the salivary glands.

Pharynx

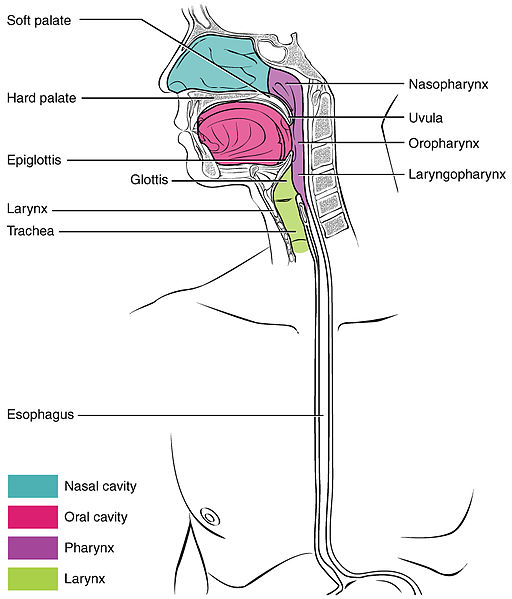

The pharynx (FAR-ĭnks), commonly called the throat, is a muscular tube lined with a mucous membrane that runs from the posterior oral and nasal cavities to the esophagus and the larynx.[10] See Figure 12.5[11] for an illustration of the pharynx.

The pharynx has three subdivisions. The superior section, the nasopharynx, is involved only in breathing and speech. The other two subdivisions, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx, are used for both functions of breathing and digestion. The oropharynx begins inferior to the nasopharynx and continues to the laryngopharynx. In the laryngopharynx, the inferior border of the laryngopharynx connects to the esophagus, whereas the anterior portion connects to the larynx.[12]

The pharynx is involved in both digestion and breathing. It receives air from the mouth and nasal cavities and food from the mouth. When food enters the pharynx, involuntary muscle contractions close a flap of tissue called the epiglottis (ĕp-ĭ-GLŎT-ĭs) to prevent food from entering the trachea and to ensure it enters the esophagus. Dysphagia (dis-FĀj-ē-ă), also called aspiration, refers to difficulty swallowing that can result in food entering the respiratory tract.

Esophagus

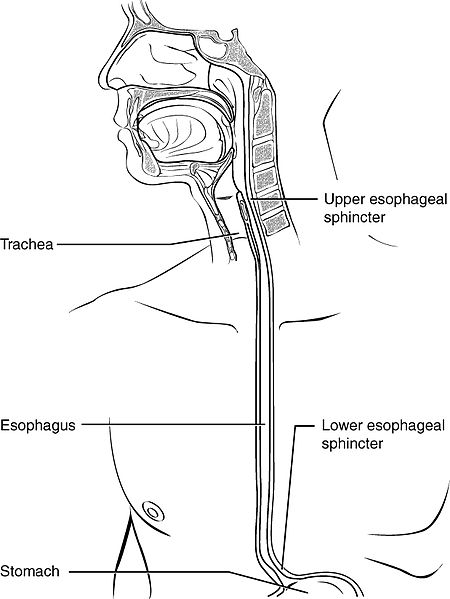

The esophagus (ĭ-SOF-ă-gŭs) is a muscular tube that connects the laryngopharynx to the stomach. It is located posteriorly to the trachea and is approximately ten inches long. See Figure 12.6[13] for an illustration of the esophagus. The upper esophageal sphincter is a muscular ring that controls the movement of food from the pharynx to the esophagus.[14]

A series of wave-like muscle contractions called peristalsis (per-ĭ-STAL-sĭs) push food through the esophagus and into the stomach. Just before the opening to the stomach is another ring-shaped muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LOH-ĕr ĭ-SOF-ă-gĕ-al SFINGK-tĕr), also known as the cardiac sphincter. Recall that sphincters are muscles that surround tubes and serve as valves, closing the tube when the sphincters contract and opening it when they relax. This sphincter opens to let food pass into the stomach and closes to keep it from backing up into the esophagus.[15]

Esophageal varices (ĕ-sŏf-ă-JĒ-ăl VĀR-ĭ-sēz) refers to an abnormal condition of swollen veins in the lower part of the esophagus.

Stomach

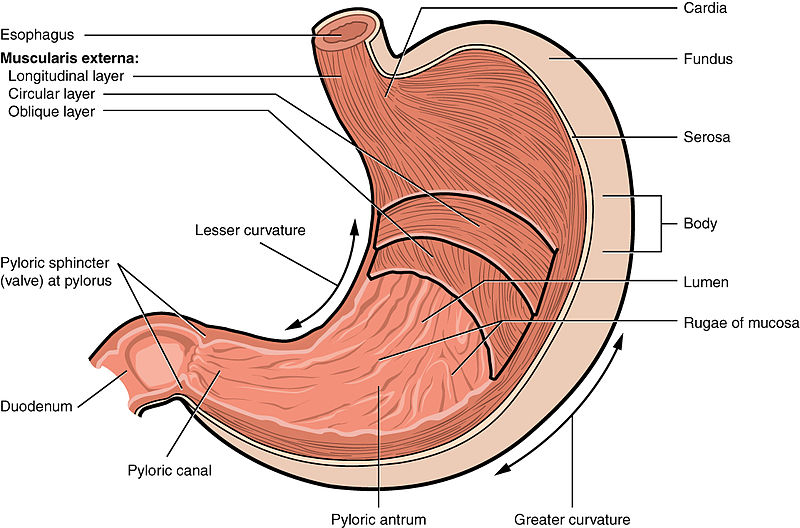

The stomach (STUM-ăk) is a sac-like organ where food is mixed with gastric juice. There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The funnel-shaped pylorus connects the stomach to the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The pyloric sphincter (pĭ-LOR-ĭk SFINGK-tĕr) is located at this latter point of connection and controls stomach emptying into the small intestine.[16] See Figure 12.7[17] for an illustration of the stomach.

The inner lining of the stomach is covered by a mucous membrane that secretes a protective coat of alkaline mucus. The mucous protects the stomach from corrosive stomach acid. Gastric glands lie under the surface of this lining and secrete a complex digestive fluid referred to as gastric juice (GAS-trĭk JOOS).[18]

Cells in the stomach lining secrete digestive hormones, such as gastrin and pepsin, as well as hydrochloric acid (HĪ-drō-klōr-ĬK AS-id). The acidity stimulates digestive hormones and also kills most of the bacteria ingested with food. A common digestive disorder called gastroesophageal reflux disease (GAS-trō-ĕ-sŏf-ă-JĒ-ăl REE-flŭks dĭ-ZĒZ) (GERD) is caused by excessive hydrochloric acid that backs up into the lower esophagus.[19] Read more information about this condition in the “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System” section.

The muscular walls of the stomach move food through the stomach and vigorously churn it, mechanically breaking it down into smaller particles.

Small Intestine

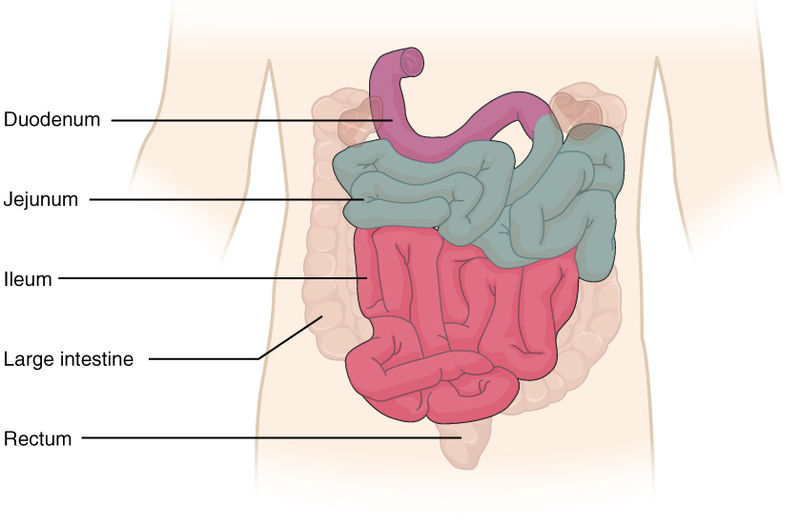

Partially digested food, called chyme (KĪM) is released from the stomach via the pyloric sphincter and enters the small intestine (SMOL IN-tĕs-tĭn), the part of the digestive tract where most of the digestion and absorption into the blood occurs. Approximately 90 percent of nutrients from food are absorbed through villi (VIL-ī), small fingerlike extensions on the inner surface of the small intestine. The small intestine is about ten feet long. Its name derives from its small diameter of about one inch, compared to the large intestine’s diameter of about three inches.[20]

The coiled tube of the small intestine is subdivided into three regions called the duodenum (dū-ō-DĒ-nŭm), jejunum (jĭ-JŪ-num), and ileum (ĬL-ē-ŭm). The ileum joins the cecum of the large intestine at the ileocecal valve. The ileocecal valve (ĬL-ē-ō-SĒ-kăl VALV) controls the flow of chyme from the small intestine to the large intestine.[21] See Figure 12.8[22] for an illustration of these regions.

Large Intestine

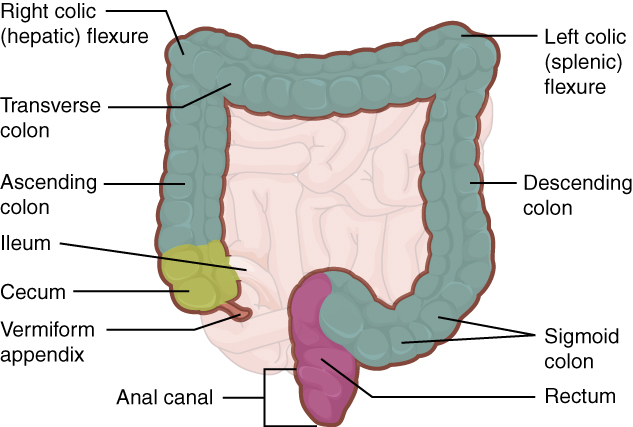

The large intestine (LARJ IN-tĕs-tĭn) runs from the cecum to the anus. The primary functions of the large intestine are to finish absorption of nutrients and water, synthesize certain vitamins, and form and eliminate feces (FĒ-sēz), also called stool. The large intestine is about one half the length of the small intestine but is called large because its diameter is three inches, about twice the diameter of the small intestine. The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal.[23] See Figure 12.9[24] for an illustration of the large intestine.

Cecum

The cecum (SĒ-kŭm) is the initial part of the large intestine. It receives the contents of the small intestine and continues absorbing water and salts. The appendix (ă-PEN-diks) is a small pouch attached to the end of the cecum. Its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of intestinal bacteria that can lead to appendicitis (ă-pen-dĭ-SĪT-ĭs). An appendectomy (ap-ĕn-DEK-tŏ-mē) is the surgical removal of the appendix.[25]

Colon

Food residue entering the colon travels up the ascending colon (ă-SEN-ding KŌ-lŏn) on the right side of a person’s abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to become the transverse colon (trans-VURS KŌ-lŏn), where it travels across to the left side of their abdomen. From there, chyme passes through another bend inferior to the spleen and down the descending colon (dĕ-SEN-ding KŌ-lŏn), which runs down the left side of the posterior abdominal wall and becomes the S-shaped sigmoid colon (SIG-moyd KŌ-lŏn).[26]

Rectum

The rectum (REK-tŭm) is the final eight inches of the large intestine. It has three folds called rectal valves that help separate feces (FĒ-sēz) from flatus (FLĀ-tŭs), commonly referred to as gas.[27]

A proctoscope (PRŎK-tă-skōp) is an instrument used by a health care provider to view the rectum.

Anal Canal

The anal (ĀN-ăl) canal is about three inches long and opens to the exterior of the body at the anus (Ā-nŭs), the end of the digestive tract. The anal canal includes two sphincters. The internal anal sphincter is made of smooth muscle, and its contractions are involuntary. The external anal sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, which is under voluntary control. Except when defecating, both sphincters usually remain closed.[28]

A hemorrhoid (HEM-ŏ-royd) is a common but abnormal condition of a distended and swollen vein in the anus or rectum.

Accessory Organs of Digestion

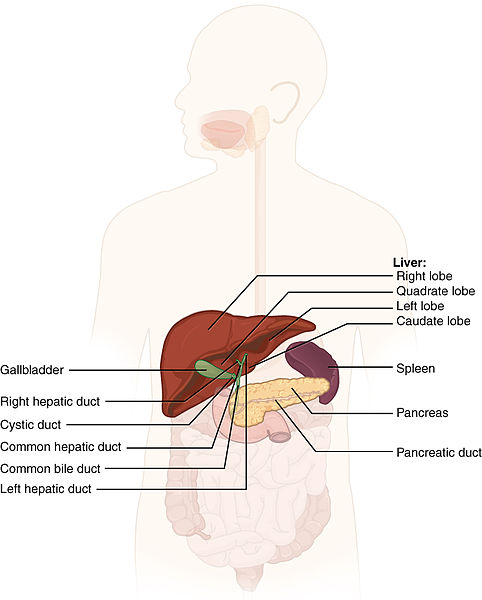

Chemical digestion in the small intestine relies on the activities of three accessory digestive organs: the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. See Figure 12.10[29] for an illustration of these digestive accessory organs. The digestive role of the liver is to produce bile and export it to the duodenum. The gallbladder stores, concentrates, and releases bile. The pancreas produces pancreatic juice, which contains digestive enzymes and bicarbonate ions, and delivers it to the duodenum.[30]

Liver

The liver (LIV-ĕr) plays many roles in digestion, metabolism, and hemostasis. The liver lies inferior to the diaphragm in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity. It is protected by the surrounding ribs. The liver is divided into two primary lobes, a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe. Hepatomegaly (hep-ăt-ō-MEG-ă-lē) refers to an enlarged liver.[31]

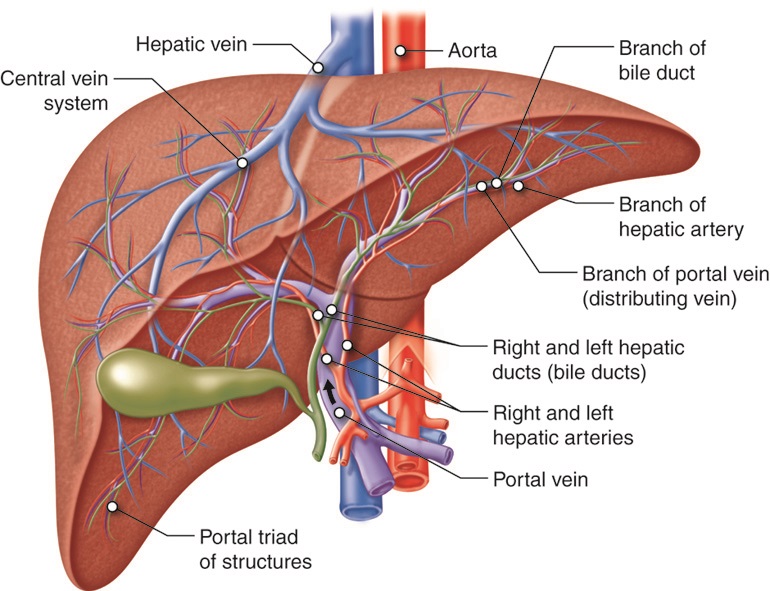

The portal vein delivers nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine to the liver. The liver absorbs and/or metabolizes nutrients, toxins, and medications. After the liver has broken down harmful substances, the by-products are excreted into the bile or blood. Bile (BĪL) is a digestive fluid produced and secreted by the liver. Bile enters the intestine and leaves the body in the form of feces. After the liver processes these substances in the blood, it releases the filtered blood through the hepatic vein that flows into the inferior vena cava. See Figure 12.11[32] for an illustration of these structures related to the liver.[33]

Bilirubin (bil-ĭ-ROO-bin) is a yellowish pigment produced by the breakdown of red blood cells that is filtered out of the blood by the liver. If a person’s liver is not functioning properly, it cannot adequately filter out the bilirubin, causing yellowing of the skin and eyes referred to as jaundice (JAWN-dĭs).[34]

In some digestive diseases, bile does not enter the intestine, resulting in white stool with a high fat content because virtually no fats are broken down by the bile. Steatorrhea (stē-ăt-ō-RĒ-ă) refers to excessive fat excreted in the stool.[35]

Pancreas

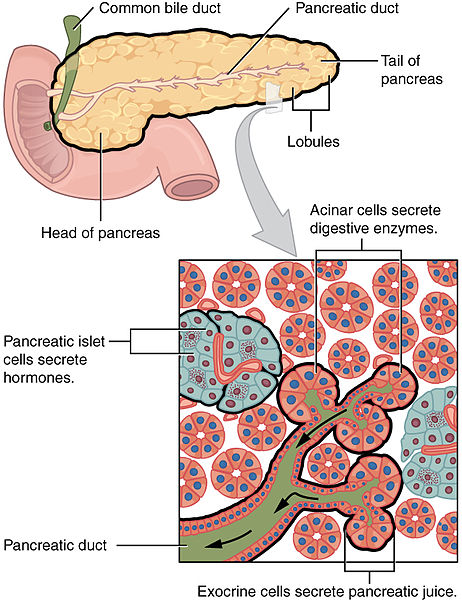

The soft, oblong, glandular pancreas (PAN-krē-ăs) lies transversely behind the stomach. Refer back to Figure 12.10 for an illustration of the location of the pancreas. The pancreas has two functions referred to as exocrine (ĔK-sŏ-krīn), meaning secreting digestive enzymes, and endocrine (EN-dŏ-krīn), meaning releasing hormones into the blood.[36]

The exocrine portion of the pancreas produces many protein-digesting enzymes, pancreatic amylase (ĀM-ĭ-lās) that digests carbohydrates, and pancreatic lipase (LĪ-pās) that digests fat. The pancreas delivers these enzymes to the duodenum through the pancreatic duct and into the common bile duct (carrying bile from both the liver and gallbladder). The endocrine function of the pancreas secretes the hormones insulin and glucagon to regulate blood glucose levels.[37] See Figure 12.15[38] for an illustration of the pancreas.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder (GAWL-blăd-ĕr) is about 3-4 inches long and is nested in a shallow area underneath the right lobe of the liver. This muscular sac stores, concentrates, and releases bile into the duodenum via the common bile duct. Refer back to Figure 12.10 for an illustration of the location of the gallbladder.[39]

Gallstones can form in the gallbladder, a condition called cholelithiasis (kō-li-lith-Ī-ă-sĭs). Inflammation of the gallbladder is referred to as cholecystitis (kŏl-ĕ-sĭs-TĪ-tĭs). Read more information about these conditions in the “Diseases and Disorders of the Digestive System” section.

- “abe85277d60c52f85be133e1b5ddc40aea009e1c.jpg” by J. Gordon Betts, et al. is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system ↵

- This image is a derivative of “3D_Medical_Animation_Oral_Cavity.jpg” by https://www.scientificanimations.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Papillae_on_tongue.svg” is a derivative work by Kjell ANDRÉ licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Salivary_glands_numbered.svg” by Goran tek-en, following request by and knowledge from Tom (LT) is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2411_Pharynx.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2412_The_Esophagus.jpg” by OpenStax College is CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2414_Stomach.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2417_Small_IntestineN.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2420_Large_Intestine.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2422_Accessory_Organs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Cenveo - Drawing Liver anatomy and vascularisation - English labels” by Cenveo is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2424_Exocrine_and_Endocrine_Pancreas.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵