Simple clothing styles, referred to as “plain” within the Quaker community, visibly distinguished 19th century Quakers from their more fashionable non-Quaker neighbors. Quaker women usually wore dresses in “drab” colors of brown or gray. They avoided lace or ribbons, and shunned all but the most simple jewelry or ornamentation. Men might wear distinctive, low brimmed hats, dark colored suits and shirts with no collars. The idea was for Friends to allow their personal clothing to reflect simple humility. A good discussion of plain dress written by Janet Frazer is on the Merion Friends Meeting website.

This clothing style made Quakers look distinctive, similar to the way Amish or Mennonite dress stands out to us today. It is documented that enslaved fugitives heading north sometimes looked out for Quakers and knew them by their clothing. Thus, Quaker “plain” dress became a component of the Underground Railroad. It is an extraordinary example of unintended consequence: the distinctive clothes were worn for one purpose – humility -but consequently aided in another – signalling they were members of an anti-slavery religious faith. It is likely “plain” dress literally saved lives during decades of Underground Railroad activity.

Wilbur H. Siebert (1866-1961) gathered a collection of escaped slaves’ narratives, putting them into a book, “The Underground Railroad From Slavery to Freedom.” The book gives many examples of Quaker efforts to aid freedom seekers. Siebert drew attention to how the distinctive clothing of Quakers played a part in the Underground Railroad, including these examples from pages 167 and 169 of his book. The first example makes clear how recognizable Quaker attire was to others. In the second example (both are shown below) it is likely that the “slave-woman” being “closely pursued” appealed to Quaker Joseph Walker because he was recognizably a Quaker and therefore would likely be an ally:

[Siebert’s Underground Railroad Slavery to Freedom, pg. 167] “John Fairfield, a Virginian Quaker, succeeded in aiding companies of slaves to escape from Washington and Harper’s Ferry by resorting to means of disguise. Among the Quakers the woman’s costume was a favorite disguise for fugitives. No one attired in it was likely to be in the least degree suspicioned of being anything else than what the garb proclaimed. The veiled bonnet also was peculiarly adapted to conceal the features of the person disguised.”

[Siebert’s Underground Railroad Slavery to Freedom, pg. 169] “One incident will suffice to show the utility of the Quaker costume: One evening Joseph G. Walker, a Quaker of Wilmington, Delaware, was appealed to by a slave-woman, who was closely pursued. She was permitted to enter Mr. Walker’s house, and a few minutes later, in the gown and bonnet of Mrs. Walker, she passed out of the front door leaning upon the arm of the shrewd Quaker.”

A $100 Reward is posted in "Genius of Liberty," a Leesburg, Virginia newspaper from September 1827 advertises for the return of "negro man" who "RAN AWAY" Amos Norris. 33 years later a man with the same name, now living in freedom in Canada, approached Quakers Dillwyn Parrish (1809-1886) and Edward Hopper (pictured above) with their wives, asking Parrish if he was from Loudoun County, Virginia. Did he get caught after this attempt, and try again until his escape was successful?

Professor A. Glenn Crothers, in an article for the North Carolina Friends Historical Society, called “I Felt Much Interest in their Welfare,” takes up the Amos Norris story:

In 1860, Philadelphia Quaker Dillwyn Parrish, accompanied by his friend and fellow Friend Edward Hopper and their wives, toured Niagara Falls. While sitting on the banks of the river, the group was approached by a stranger, “a colored man” who “enquired if I was from Loudoun Co. Va.” Informed that he was not, the stranger “apologized,” explaining that he thought Parrish “resembled Mr. Saml. Janney” of that county. Though Janney and Parrish looked not at all alike, Parrish was a close friend of Janney’s, and, as Parrish later recalled, this “interesting information” sparked “a considrable conversation” between the man, Amos Norris, and Parrish’s party. Norris informed Parrish and his party that he was a former resident of Loudoun County who had fled in 1850 and now resided in Canada.

By Parrish’s own reckoning, he and Samuel Janney “looked not at all alike” yet somehow to Amos Norris, they “resembled” one another. The most likely, and perhaps only reason for any resemblance Dillwyn Parrish had with fellow Quaker Samuel Janney would have been the Quaker clothing the group visiting Niagara Falls was wearing. Norris goes on to request Samuel Janney’s contact information; it turned out his sister is living with the Janneys, and he wanted to write a letter to her.

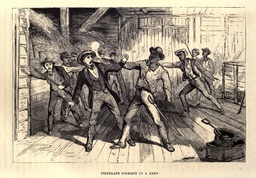

Unfortunately there are also examples, within the history of the Underground Railroad, of men pretending to be sympathetic Quakers in order to entrap escaping slaves. An example of this is found in William Still’s “Underground Railroad,” his book compiled from interviews with former slaves. Sizeable rewards were offered for “runaways,” and it is likely the white men in the following example were motivated to capture Wesley Harris and his friends in order to obtain reward money. Here is an excerpt of Harris’ experience, as he later told it to William Still:

“November 2d, 1853.—Arrived: Robert Jackson (shot man), alias Wesley Harris; age twenty-two years; dark color; medium height, and of slender stature.

“One Saturday night, at twelve o’clock, we set out for the North. After traveling upwards of two days and over sixty miles, we found ourselves unexpectedly in Terrytown, Md. There we were informed by a friendly colored man of the danger we were in and of the bad character of the place towards colored people, especially those who were escaping to freedom; and he advised us to hide as quickly as we could. We at once went to the woods and hid. Soon after we had secreted ourselves a man came near by and commenced splitting wood, or rails, which alarmed us. We then moved to another hiding-place in a thicket near a farmer’s barn, where we were soon startled again by a dog approaching and barking at us. The attention of the owner of the dog was drawn to his barking and to where we were. The owner of the dog was a farmer. He asked us where we were going. We replied to Gettysburg—to visit some relatives, etc. He told us that we were running off. He then offered friendly advice, talked like a Quaker, and urged us to go with him to his barn for protection. After much persuasion, we consented to go with him.

“Soon after putting us in his barn, himself and daughter prepared us a nice breakfast, which cheered our spirits, as we were hungry. For this kindness we paid him one dollar. He next told us to hide on the mow till eve, when he would safely direct us on our road to Gettysburg. All, very much fatigued from traveling, fell asleep, excepting myself; I could not sleep; I felt as if all was not right.

“About noon men were heard talking around the barn. I woke my companions up and told them that that man had betrayed us.”

The rest of Wesley Harris’ story can be read here.

Men and women escaping slavery sometimes relied on aid from strangers. But how to identify sympathetic strangers? The great majority of white Southerners supported the institution of slavery and consequently had to be avoided. Quakers, however, were known to be both anti-slavery in their beliefs and distinctive in their appearance. Quakers could be identified and approached by men and women in the brave act of escape. Sometimes the help of drab, plain dressed strangers made the difference between failure or a successful bid for freedom.

Pingback: Amos Norris on the Road to Freedom: from Loudoun County to Niagara Falls – Nest of Abolitionists