This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Hans Christian Andersen and the Round Tower

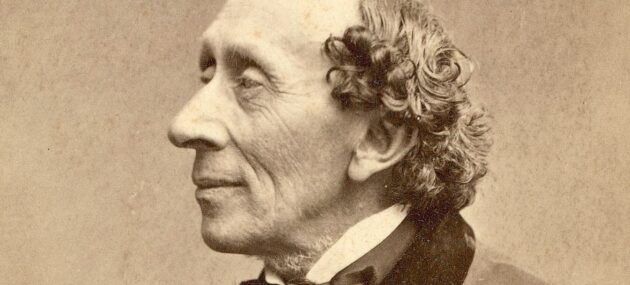

When Hans Christian Andersen (1805-75) travelled from the city of Slagelse to Elsinore at the age of 21 to continue his schooling there, he described his travel observations in a letter. He thought the letter was so well written that he immediately copied it and sent it to several of his acquaintances.

Professor of literature Rasmus Nyerup also received a copy. Like Andersen, Nyerup came from the island of Funen. He had greeted the emerging poet in Copenhagen just after his arrival to the city some years earlier and had allowed him to use the books in the University Library, which was located in the hall above the Trinity Church and accessible through the Spiral Ramp – provided that Andersen put the books properly away after use. Apparently, Nyerup liked the letter, too, for without Andersen’s knowledge, he published an excerpt of it in the leading periodical Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn.

“It was neither the first nor the last time the Round Tower was mentioned in Hans Christian Andersen’s writings”

All of the addressees were now able to read the account of the journey, which they believed had been written especially for them, in the periodical. Accordingly, several of them pointed this out to the letter writer. “My friends from Slagelse therefore thanked me for the interesting letter they had received and afterwards read in print,” Hans Christian Andersen subsequently notes.

One might think that the poet had learned his lesson from the embarrassing experience by now, but it was not the case. Many years later, he made use of the same literary device once again, later to be known as self-plagiarism. And this time, the Round Tower was more directly involved.

Down and Up

It was neither the first nor the last time the Round Tower was mentioned in Hans Christian Andersen’s writings. One of Andersen’s early poems, “The Ghastly Hour” (”Den rædselsfulde Time”) from 1827, unfolds a dreamscape where the poem’s narrator wakes up in the University Library during the midnight hour and to his horror finds that “the Round Tower no longer exists”. What is left is the lurking abyss in place of the safe descent to the street level.

The following year the poem “The Rhyme-Devil” (“Rime-Djævelen”) was published. Here the course of events takes place in the opposite direction, namely “up in the inner scrolls of the tower” at the end of which the magnificent view saves the poem’s narrator from suicidal thoughts. Incidentally, both poems were published for the first time in the literary magazine Kjøbenhavns flyvende Post on whose vignette the Round Tower features among other towers of Copenhagen.

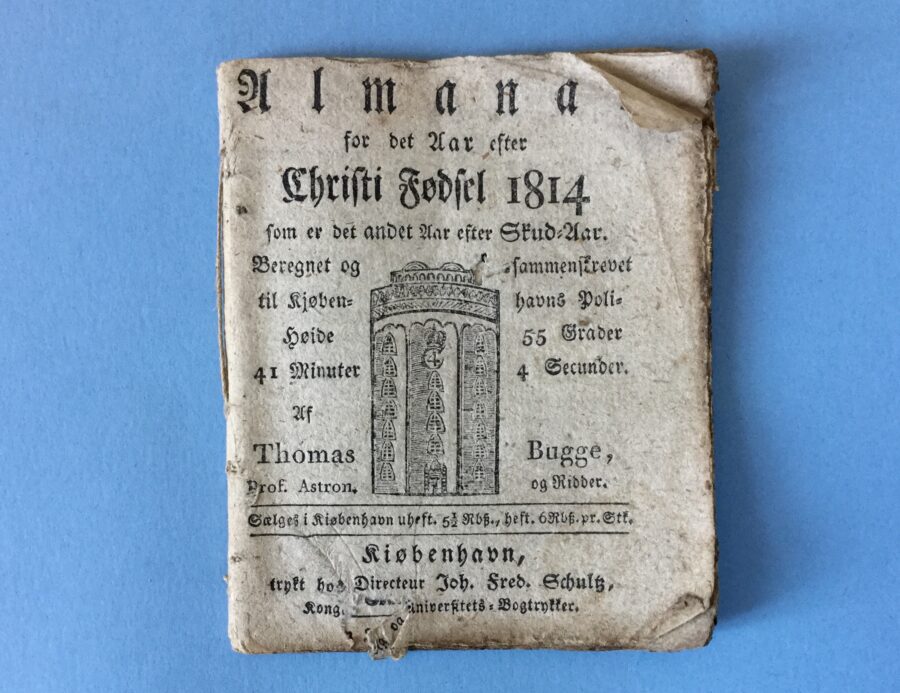

Part of the story in the novel To Be or Not To Be (At være eller ikke være) from 1857 also transpires in the Round Tower. But the best-known instance of the tower appearing in Hans Christian Andersen’s poetry is undoubtedly the comparison that is being made in the fairy tale “The Tinderbox” (“Fyrtøiet”). As is well-known, this is where the largest dog has “eyes as big as the Round Tower!” without it being further explained whether the size refers to the tower’s height, its diameter, or, as has also been suggested, to two small cupolae on the Observatory at the top of the tower. Contrary to the actual facts at that time, they were depicted in the illustration of the Round Tower, which appeared on the front page of the University of Copenhagen’s almanac in the years from 1745 to 1850. Thus, also in 1835 when “The Tinderbox” was released.

Listen to our audio story about Hans Christian Andersen’s relationship with the old tower.

The Danish Poet’s Tree

It is also a comparison with the Round Tower that Hans Christian Andersen becomes so fond of that he duplicates it in several letters, just as he did after the trip to Elsinore.

Andersen not only payed visits to Danish manor houses, he was also a welcome guest in the exalted circles in Germany. In almost disbelief, he thus notes in a letter from 1844 that, “it is actually the case, that I am the most famous Danish poet in Germany, the one that people prefer reading”. Amongst the people who enjoyed his work were the Serre family, owners of Maxen Castle just south of Dresden. The castle became a place where he and several other German and Scandinavian artists frequently stayed as guests.

During one of his visits at the castle, he found a small larch tree thrown away on the road while he was out on a stroll. He planted the tree in a crevice at the edge of a cliff. The tree grew large and was provided with the inscription “The Danish Poet’s Tree”. It was even told that when a birch tree standing next to it threatened to take all the light, it was struck by lightning and completely splintered, while the larch tree remained untouched.

Up and Down

Hans Christian Andersen makes a visit to his tree again in 1855, and one dares say that it is something to write home about. He mentions it no less than four times in his correspondence. But if one of the addressees had published the letter this time, the others would have had reason to be confused since Andersen cannot decide on how deep the abyss beneath the tree is.

“After this high jump it seems sensible to come back down to earth”

“When one stands by [my] tree, the road beneath is far away, so far that it would take three times the length of the Round Tower to reach it,” he writes on 8 July 1855. Three days later he corrects himself and writes, “The height of the cliff, on which the tree is sited, is two times that of the Round Tower”. Yet another week later he notes, “The tree is situated so far above the depths below that it would take two or tree times the length of the Round Tower to reach it”. And one month later the Round Tower has either diminished or the recollection has become blurred. “The little larch tree I was referring to, has now become a big tree – three times taller than me. A mountain lake is landscaped around it, roses have been planted and the view from the cliff where the tree stands can be taken in at a height ten times that of the Round Tower”, as Andersen writes.

After this high jump it seems sensible to come back down to earth, which the poet also did three years later in the fairy tale “The A-B-C Book” (“ABC-Bogen”). Here, he explains the letter “R” by referring to the Round Tower with the following words:

”One may be round as the Round Tower and well extended,

But that doesn’t mean one is well descended!”