Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review highlights current concepts in the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).

Recent Findings

A new scoring system, the ABCD-10, was recently developed to better estimate mortality among SJS/TEN patients. Supportive care remains the mainstay of treatment, and includes wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, management of medical co-morbidities, and infection control. The value of adjuvant therapy remains unclear, but new recent retrospective studies suggest that the combination therapies may be efficacious. Recent prospective studies investigating cyclosporine and etanercept have shown promise in the treatment of SJS/TEN.

Summary

SJS and TEN are severe mucocutaneous drug reactions associated with high morbidity and mortality. Supportive care is the most universally accepted therapy, although specific strategies may vary among institutions. Adjuvant therapies include corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, TNF alpha inhibitors, and plasmapheresis but prospective data is still lacking. Clinical trials that may better elucidate their efficacy are currently under way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are severe, mucocutaneous drug reactions associated with high mortality and morbidity. Both are part of a disease continuum and are distinguished from each other based on severity and the percentage of body surface area (BSA) involvement [1]. Patients with SJS typically develop a deeply erythematous exanthematous eruption, mucosal and cutaneous bullae, and desquamation, with less than 10% BSA involvement. Patients with TEN have more widespread, rapidly evolving skin sloughing, with greater than 30% BSA involvement. Those with cutaneous involvement between10 and 30% BSA involvement are considered to have SJS/TEN overlap. Although in practice, our approach to SJS may be slightly different from our approach to TEN, for the purpose of this review, the term “SJS/TEN” includes all three disease states.

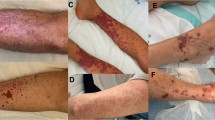

Patients with SJS/TEN may experience fever and flu-like symptoms early in the course of their disease. Initial skin findings may include an exanthematous eruption, deep red macules and purpura, atypical targetoid lesions, and/or generalized erythema. Patients may also complain of skin tenderness. These are followed by a painful, generalized vesiculobullous eruption and desquamation (Fig. 1). Full-thickness epidermal necrosis leads to splitting of the sub-epidermal layers [2]. Application of shear forces on seemingly intact skin induces epidermal separation and sloughing—a phenomenon known as Nikolsky sign [3]. Mucosal involvement (oral, ocular, and/or genital) occurs in 90% of cases and can precede the generalized eruption [4]. SJS/TEN is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Extensive skin detachment may lead to insensible fluid loss and a high risk of infections, often resulting in severe multi-systemic derangements.

The pathogenesis of SJS/TEN is still unclear, but several HLA subtypes have been associated with a predisposition for developing SJS/TEN to specific medications [5•, 6]. Keratinocyte cell death in SJS/TEN is caused by a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction, mediated in part by cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells that release granulysin and activate transmembrane death receptors [7, 8]. Engagement of the programmed cell death surface receptor Fas by its ligand induces keratinocyte apoptosis [8, 9]. More recent studies also point to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class 1 restricted cytotoxic T cell activity against the offending drug [10,11,12]. Histopathology typically demonstrates epidermal necrosis and keratinocyte apoptosis with basket weave stratum corneum and separation of the dermis and epidermis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate within the dermis [13]. Our current understanding of the pathogenesis of SJS/TEN is central in the development of therapeutic approaches to this rare but potentially fatal condition.

The relatively rare occurrence of SJS and TEN presents challenges for conducting prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trials to investigate therapies. While SJS is more common than TEN, the pooled incidence is thought to be between one to ten cases per million people per year [14,15,16,17,18]. The most recent studies from the UK, Germany, and Korea point to an incidence of 5.7 or fewer per million people per year [19•, 20•, 21•]. Studies from the USA found an incidence of 5.3 cases (SJS) and 0.4 cases (TEN) per million children per year [22]. The average age of patients with SJS/ TEN varies, but the median age of adult patients in a recent retrospective, multicenter study from the USA was estimated at 49 years (SD 19.2). [2, 23•] Many of these patients have associated co-morbidities, including active infection, diabetes mellitus, active malignancy, kidney, pulmonary and heart disease, seizure disorder, and HIV infection. The natural history of SJS/TEN among pediatric patients is different from that of adults [24]. Pediatric patients with SJS/TEN tend to have better outcomes and lower mortality compared with adults. Although there are similarities in how we approach SJS/TEN in adults and children, the treatment of pediatric SJS/TEN requires a separate discussion.

Medications remain the major cause of SJS/TEN, with infections such as mycoplasma pneumonia and herpes simplex comprising a smaller population [23•]. Antibiotics (especially trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), antiepileptic medications, allopurinol, and NSAIDs remain commonly implicated causes of drug-induced SJS/TEN [23•].

Mortality ranges from about 24% in SJS to about 49% in TEN after 1 year [25]. A 2017 study using data from the US Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2009 to 2012 estimates inpatient mortality rates to be 4.8% for SJS, 14.8% for TEN, and 19.4% for SJS/TEN overlap [22•]. Recent findings point to a reduced mortality, likely due to improved SJS/TEN management, overall improvements in health care, and/or other patient factors [23•].

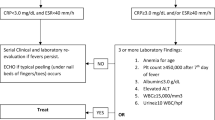

The SCORTEN is a validated, prognostic scoring system that estimates mortality based upon clinical features and laboratory values on days 1 and 3 of hospitalization [26] (Table 1). New evidence suggests that the SCORTEN may overestimate mortality in contemporary patients [23•, 29,30,31]. An updated model, the ABCD-10, has been proposed, based on a retrospective, multicenter study conducted in the USA (Table 1) [27•]. Further research is required to determine the generalizability of this updated model. These scoring systems are important not only for guiding management but also in the conduct of both retrospective and prospective studies on SJS/TEN. Due to the relative rarity of these severe drug reactions, and inherent challenges in designing comparative trials, studies investigating the efficacy of therapies for SJS/TEN typically utilize differences in standardized mortality ratio as a primary outcome measure. That is, the efficacy of a treatment modality for SJS/TEN is assessed by comparing the observed, vs the SCORTEN-predicted mortality, among who received that treatment.

Management of SJS/TEN is divided into two arms: supportive care and adjuvant medication therapies. There remains an unmet need for good quality, prospectively collected data that informs us about the appropriate treatment for SJS/TEN. National societies have developed consensus guidelines, but also highlight this knowledge gap [32•, 33•, 34•]. This review serves to provide an update on the literature for the management of SJS/TEN.

Supportive Care

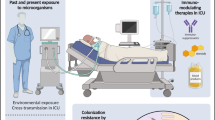

Supportive care remains the mainstay of treatment for SJS/TEN. Supportive management of SJS/TEN should include removal of inciting drug, transfer to appropriate level of care, and multidisciplinary management medical co-morbidities, fluid and electrolyte balance, airway, nutrition, and temperature (Fig. 2). Wound care, pain control, and prevention of infection are also essential [35•].

Initial Management

The first and most crucial step in a patient presenting with SJS/TEN is discontinuation of the culprit drug. Prompt withdrawal has been shown to lead to better outcomes and a reduced risk of death [36•]. Patients should be admitted to the hospital if SJS/TEN is suspected, and prognosis evaluated using SCORTEN. The SCORTEN score can be helpful in determining whether a patient’s disease is severe enough to require a specialized intensive therapy or burn unit, or whether a nonspecialized ward is sufficient. Any pre-existing or associated co-morbidities need to be identified and addressed. The need for expertise and resources for advanced wound care, fluid and electrolyte resuscitation, and advanced medical care should be considered in deciding where to admit the patient. Generally, patients with involvement of large areas of epidermal loss (> 10% body surface area) or a high SCORTEN score should be transferred to a specialized intensive care or burn unit [32•]. Patients with SJS/TEN are also more likely to have underlying co-morbidities that are risk factors for both developing severe cutaneous drug reactions and poorer outcomes—HIV, malignancies, autoimmune disease, viral infections, renal, pulmonary and cardiac disease, among others. Patients may also develop involvement of other organ systems as part of their SJS/TEN [37•]. Access to expertise and appropriate medical monitoring and support depending on medical risk factors is equally crucial in the care of patients with SJS/TEN.

Wound Care

Wound care is an essential part of caring for patients with SJS/TEN. It helps preserve the epidermis, prevent infection, and minimize water loss [31]. An optimal approach to wound care in these patients has yet to be determined, and strategies, choice of dressings, can differ among various medical centers.

Our overall approach to wound care in SJS/TEN is the same as our approach to other immune-mediated conditions of epidermal separation. We prefer the use of simple dressings composed of bland ointments such as white petrolatum and nonstick dressings. Other authors prefer the use of advanced dressings, such as fiber, biologic, and synthetic dressings, and note that patients treated with advanced dressings may require fewer dressing changes. There does not appear to be a significant difference, however, in the healing time among SJS/TEN patients treated with simple vs advanced dressings [38•, 39•]. In our hands, the frequency and choice of dressings depend on the extent and characteristics of the wounds (i.e., how exudative the wounds are, whether or not there are signs of superimposed infection).

Certain medical centers or burn units follow an aggressive debridement policy, in which wounds are actively debrided and necrotic epidermis removed either surgically or through whirlpool therapy [40•]. This kind of aggressive surgical approach can facilitate adherence of modern dressings such as allografts, xenografts, or BIOBRANE to the underlying dermis, but is also associated with an increased risk of infection and hyperpigmentation [30•, 41•]. Our preferred approach, on the other hand, is a conservative strategy of leaving the detached skin in situ to act as a biologic dressing unless there are clear signs of infection or necrosis [41•]. In a recent observational study in a burn unit setting, a more conservative wound care program that minimizes or avoids shear stress on wounds, and leaves skin intact, was associated with better than expected rates of survival and re-epithelialization [42]. In addition, the patients required fewer dressing changes, and there was a reduced need for operating room time. The cost of care was also reduced. Wound management must therefore be tailored to the patient’s requirements, including the wound extent and characteristics as well as the patient’s medical status.

Fluids, Electrolytes, and Environment

Patients with SJS/TEN should have careful management of their intake and environment. Patients can have imbalances in fluids and electrolytes due to dermal exfoliation, similar to burn victims. However, replacement volumes are approximately one-third lower than those needed for burn victims [43]. The environment should be kept at an optimal temperature, generally at 30–32 °C to prevent excess caloric expenditure [2]. SJS/TEN patients should be given oral nutrition as soon as possible and continued throughout the acute phase, via nasogastric tube if necessary, in order to maintain caloric needs [17, 32•].

Infection Control and Management of Co-morbidities

Patients with SJS/TEN can develop other organ co-morbidities. The development of associated infection and sepsis, however, remains the most prominent causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with SJS/TEN [2, 17]. In a recent retrospective study, a low hemoglobin (< 10 g/dL) on admission, pre-existing cardiovascular disease, and > 10% BSA involvement on admission were predictors of the development of bacteremia [44•]. Nonetheless, prophylactic antibiotics are not regularly used and have not been shown to improve outcomes [45]. Management primarily revolves around careful clinical assessment and appropriate wound care and sterile handling. Antiseptic solutions can also be used for disinfection, in conjunction with wound care materials [32•], as long as one is mindful of the risk of systemic absorption when used in large, denuded areas. Cultures of the skin, blood, catheters, and gastric or urinary tubes should be obtained as medically indicated, with other authors recommending that this be done at 48-h intervals [2, 46]. Signs of infection include visible superinfection of skin lesions, increase in quantity of bacteria on culture, a sudden decrease in temperature, or deterioration of patients’ condition [2]. Hypothermia and a pro-calcitonin > 1 μg/L at the time of blood culture was found to be predictive of bacteremia [44•]. Other more subtle signs of infection including neutrophilia or increased C reactive protein can indicate the need for systemic antibiotic therapy [32•].

Prevention of Sequelae

Special care must be given to avoid ophthalmologic and urogenital complications. A careful history and physical examination should include evaluation of these organ systems, as regular monitoring and early detection is very important to prevent severe irreversible consequences [35•]. A 1997 retrospective study on SJS/TEN found that 12.5% of its 40 participants had chronic gynecological sequelae, and that these cases often could be successfully corrected with appropriate intervention. [47] Women with vaginal involvement of SJS/TEN can develop introital stenosis and labial agglutination with histological findings of vulvovaginal adenosis [48]. These changes commonly lead to functional impairments such as dyspareunia, bleeding, and urinary obstruction, and tissue metaplasia carries a risk of malignant transformation [49]. Strategies to prevent these long-term sequelae include topical glucocorticoids as first-line therapy, vaginal molds to disrupt adhesion formation, and menstrual suppression [48]. Urology specialists may also be consulted to check for urogenital involvement.

Ocular involvement occurs in about 80% of patients with SJS/TEN is varied and can range from a mild acute conjunctivitis to severe pseudomembranous ulcers [50]. The conjunctiva, cornea, and anterior chamber may be affected causing symptoms of pain and photophobia. The SCORTEN score used to predict mortality in SJS/TEN patients does not appear to correlate with the development of ocular complications in several studies, and so it is important to monitor closely for ocular involvement regardless of SCORTEN value. [51, 52] Long-term sequela occurs in 50–90% of patients and includes pain, dry eye, trichiasis, neovascularization of the cornea, keratitis, and scarring and formation of synechiae between the conjunctiva and eyelid [53, 54]. To prevent or reduce these sequelae, patients should be referred to an ophthalmologist for a comprehensive evaluation and aggressive, early treatment. Ocular involvement is typically graded from none to severe (grades 0–3) in effort to both assess the severity of involvement and guide therapy [55]. Lubrication drops and close monitoring are recommended for patients with no initial eye involvement (grade 0), as these patients can still have long-term complications [53]. Patients with conjunctival hyperemia (grade 1) require topical corticosteroid and antibiotic preparations. For patients with involvement of the bulbar conjunctiva or pseudomembrane formation (grades 2 and 3), amniotic membrane transplantation is added to the treatment armament and is shown to reduce sequelae in case studies and a randomized control trial [56, 57]. In all patients, saline rinses can also be initiated as a supportive measure to clear inflammatory debris from the eye [58]. To prevent scarring and loss of visual acuity, it is critical that these measures are taken early in the disease course.

Pain Control and Emotional Support

Many patients have significant pain, especially at sites of epidermal detachment. Mild pain can be controlled with acetaminophen, supplemented with opiate-based therapy for more severe pain [32•]. Additionally, patients with SJS/TEN can have psychological sequelae and reduction in quality of life [59]. Clinicians should keep this in mind and provide appropriate emotional support and information for patients and their families.

Adjuvant Therapy

In addition to supportive therapies, there is an increasing interest in adjuvant medical therapies that may speed re-epithelialization and reduce mortality in patients with SJS/TEN. In spite of the lack of conclusive data on the benefit of adjuvant pharmacologic therapy for SJS/TEN, a recent multicenter retrospective study demonstrated that the majority of patients are treated with pharmacologic therapy (70.7%) vs supportive care alone (29.3%) [23•]. Therapies such as cyclosporine, corticosteroids, IVIG, anti-TNF-alpha antibodies, and plasmapheresis, used alone and in combination, have shown mixed results in various studies (Tables 2 and 3). Most of the data addressing the use of adjuvant therapy for SJS/TEN is derived from case reports/series and retrospective studies, or non-comparative, small, prospective clinical trials. An exception is a recent open-label, randomized clinical trial comparing the use of etanercept with systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of SJS/TEN [68•]. Analysis of outcomes in most of these studies relies on differences between the observed mortality rate and the predicted mortality by SCORTEN. As a result of these limitations, there continues to be little consensus among experts on the ideal adjunctive therapy for SJS/TEN. In one of the rare, prospective, randomized clinical trials performed, the use of thalidomide for SJS/TEN was associated with increased mortality. It is therefore firmly contraindicated for use in SJS/TEN.

Corticosteroids

The use of systemic corticosteroids in patients with SJS/TEN remains controversial. In our practice, we may consider the use systemic corticosteroids for certain SJS patients who have milder disease. Although some retrospective studies have shown lower than expected mortality rates among patients with SJS/TEN who were treated with systemic corticosteroids, other studies have shown no significant benefit (Table 3). More recent retrospective data suggests that corticosteroids may be more useful in combination with other pharmacologic therapies (Table 3). There is also evidence that short-term, high-dose pulse corticosteroids may improve outcomes [63, 77]. Potential adverse effects of steroid use include sepsis, skin infection, slowed epithelialization, and increased protein catabolism. Systemic corticosteroids are relatively contraindicated for patients with widespread skin detachment [78].

In a systematic review published in 2011, 20 of 128 children in their included studies received a short duration of prednisolone, prednisone or methylprednisone. There were no deaths reported among these 20 patients, although 5 of the 20 had mild skin infections [77]. The 2013 RegiSCAR examined a registry of 442 patients and did not find a survival advantage for systemic corticosteroids, or any other adjuvant therapies for that matter [25]. This was a departure from the 2008 retrospective EuroSCAR study, which showed a potential benefit for corticosteroid use in 281 patients [79]. In another 2011 systematic review, mortality was similar to those predicted by SCORTEN in corticosteroid and supportive measures group [66]. More recently, a 2017 meta-analysis of data including 1209 patients demonstrated a decreased risk of death in patients treated with corticosteroids and supportive therapy compared with supportive therapy alone [64•]. There is also support for use of a short duration (3 days) of high-dose pulsed corticosteroids early in the disease course to decrease mortality, slow disease progression, and speed healing [63, 77].

Cyclosporine

As a stand-alone therapy, cyclosporine has more robust evidence for improved outcomes for SJS/TEN among adjuvant therapies. Cyclosporine inhibits interleukin-2 mediated T cell activation, and may also inhibit apoptosis by repressing NF-kB activation [65]. Adverse side effects from cyclosporine may include leukoencephalopathy, neutropenia, pneumonia, and nephropathy.

A 2018 meta-analysis of nine retrospective and prospective observational studies found that the observed mortality among SJS/TEN patients who received cyclosporine was approximately 70% less that predicted by SCORTEN [80•]. A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis also found decreased mortality in patients who were treated with cyclosporine compared with IVIG, consistent with findings from a 2014 retrospective review [81•, 82]. Other recent studies also show benefits for patients treated with cyclosporine [83•, 84]. In a review of data from 93 patients who received either cyclosporine or systemic corticosteroid therapy, investigators found that patients who received cyclosporine had complete re-epithelialization of their skin compared with those treated with systemic steroids (9.6 vs 14.1 days, respectively) [69]. Hospital stay of patients in the cyclosporine group was 7 days shorter than those in the corticosteroid group, although this was not statistically significant. In a case series, three pediatric patients who had rapid improvement and near complete resolution 10–15 days after being given 3 mg/kg/day for 7–21 days [85•]. Not all data is supportive, however, as one recent retrospective cohort did not demonstrate a benefit for patients treated with cyclosporine [86•].

An open-label, uncontrolled, phase II trial of 3 mg/kg/day of oral cyclosporine for 10 days given to 29 patients with SJS, TEN, or overlap SJS/TEN showed a modest reduction in observed mortality compared with the SCORTEN prediction, and re-epithelialization within 12.4 ± 7.7 days [72]. In another uncontrolled open-label study, 11 patients with SJS, TEN, or overlap SJS/TEN were given oral cyclosporine, 3 mg/kg per day for 7 days and then tapered over another 7 days. Patients had improved time to re-epithelialization, reduced hospital stay, and lower mortality when compared with historical data from corticosteroid-treated patients at the same institution [87].

Human Intravenous Immune Globulin

Human intravenous immune globulin (IVIg) is used for treatment of a variety of autoimmune conditions. Autoantibodies against Fas are thought to interfere with Fas-FasL-mediated apoptosis thereby slowing progression of SJS/TEN [9]. In the USA, this treatment modality is commonly used for patient with a more severe disease with higher median BSA involvement [88•]. Risks of this therapy include acute renal failure, thrombotic complications and hemolysis. Caution should be used with elderly patients and patients with cardiovascular or renal disorders.

Studies that address the efficacy of IVIg monotherapy for SJS/TEN have had mixed results. In the early 2000s, there were several studies that had showed improved survival among SJS/TEN patients who were treated with high-dose (2 g/kg or more) IVIg significantly improved survival with high doses [9, 71, 89,90,91]. A 2011 systematic review of treatments for SJS and TEN demonstrated 24% mortality rate for patients treated with IVIg compared with 27% for those treated with supportive therapy only [66]. The observed mortality in the IVIG group, however, was still lower than mortality as predicted by SCORTEN [66]. A 2012 systematic review that included 17 studies showed that adults who received high-dose IVIg had a decreased mortality compared with those who received low-dose IVIg [24]. This association with IVIg and mortality benefit, however, did not hold when this was subjected to a multivariate regression model. In that same systematic review, none of the pediatric patients who received IVIg died, but pediatric patients with SJS/TEN may have better outcomes overall compared with adults. A 2015 meta-analysis that included data from 391 patients, however, found no difference in mortality for the IVIG group compared with the supportive care group [76]. However, the authors did find a significant association between increasing doses of IVIg and improved mortality when they subjected their data to further analysis. Zimmerman et al. found no reduction in mortality compared with supportive therapy alone in a 2017 meta-analysis of 215 patients treated with IVIg [64•]. More recent retrospective data suggests that patients treated with a combination of IVIg and corticosteroids may have better outcomes that those treated with either therapy by itself. In a 2018 multicenter study of 377 patients from the USA, patients who received a combination of IVIG and corticosteroids had a greater reduction in their observed vs SCORTEN-predicted mortality, when compared with patients who received either IVIG or corticosteroids alone [23•]. Prior studies support these findings of reduced mortality and enhanced disease resolution in patients treated with a combination therapy IVIg therapy [79, 92, 93]. A 2016 meta-analysis for IVIG and corticosteroid combination therapy found benefits in hospital stay but not mortality [94•]. Dosing and duration of combination therapy was different for each study.

TNF-α Inhibitors

TNF-α is potentially upregulated in TEN and thought to promote apoptosis. TNF-α monoclonal antibody (infliximab) and TNF-α decoy receptor (etanercept) that target TNFα are being actively explored as potential therapies for SJS/TEN. Potential adverse effects include sepsis and respiratory failure. In case reports, 5 mg/kg of infliximab immediately halted the progression of skin detachment and induced re-epithelization within 2–10 days [28, 60,61,62, 95]. Other case reports have shown a benefit from a single 50-mg subcutaneous injection of etanercept [67]. In a landmark randomized, unblinded, comparative, clinical trial, 96 patients with SJS/TEN received either etanercept 25 mg (or 50 mg if their body weight was > 65 kg) by subcutaneous injection twice a week or 1–1.5 mg/kg/day IV prednisolone until their skin lesions were healed [68•] . Patients treated with etanercept had improved mortality compared with patients treated with corticosteroids. In addition, patients who had > 10 BSA involvement had a shorter median time to complete healing when they were treated with etanercept vs corticosteroids (14 vs 19 days, respectively).

Other Therapies

Other therapies such as plasmapheresis, granulocytic-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and thalidomide have been tried for the treatment of SJS/TEN.

Plasmapheresis was proposed as a mechanism for removal of cytotoxic mediators and drug metabolites. Complications from this procedure depend largely on the medical status of the patient and the type of fluids and plasma replacement used, along with infection risk from venous access. A prospective study including 28 patients with SJS/TEN demonstrated that patients who received plasmapheresis had more rapid improvement in their severity of illness score over 20 days compared with the non-plasmapheresis group [70•]. In addition, investigators did not observe any significant difference in their outcome measures among patients who received plasmapheresis as monotherapy vs those who received concomitant IVIg or corticosteroids. An earlier case series, on the other hand, suggested no improvement in mortality, length of hospital stay, or time to re-epithelialization [73]. Plasmapheresis may nevertheless be an option, however, among patients with refractory SJS/TEN [74, 75].

G-CSF is thought to have bioregenerative and immunomodulating properties and currently under investigation. Thalidomide is a potent TNF-α inhibitor. Unlike infliximab and etanercept, it is firmly contraindicated for the treatment of SJS/TEN, as it was shown to increase mortality in a randomized placebo-controlled trial in patients with TEN [96, 97, 98•, 99•, 100, 101•, 102•].

Ongoing and Future Clinical Trials

There is a critical need for interventional studies that can determine the true effect of adjuvant therapies on mortality, length of hospital stay, time to re-epithelialization, and other important outcomes. Several studies are on the horizon. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute is planning a multicenter, phase III clinical trial to determine if either cyclosporine or etanercept therapy improves short-term outcomes in SJS/TEN compared with supportive care alone (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02987257). Massachusetts General Hospital is sponsoring an upcoming multicenter, prospective, observational study to investigate the efficacy of cyclosporine, IVIG, etanercept, and corticosteroids for patients with SJS/TEN (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03585946). A phase 4 trial to determine the efficacy of four days of 5 μg/kg of recombinant granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) vs placebo, among patients with TEN, is in the recruiting phase (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02739295) as is a pilot, comparative, trial to investigate the efficacy of oral isotretinoin (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02795143).

Conclusion

SJS/TEN is a rare but life-threatening condition with a potentially high morbidity and mortality. Tools such as the SCORTEN and ABCD-10 may be used to predict mortality. Management of SJS/TEN remains a challenge and there continues to be a limited consensus due to a lack of prospective studies for this serious but rare entity. A multidisciplinary approach, early recognition of the condition, and removal of the offending agent, along with aggressive supportive therapy, significantly improve outcomes. There may be benefits to using adjuvants alone or in combination, but they must be used cautiously, with consideration of the individual patient’s medical status and potential adverse effects. Majority of the data addressing the use of adjuvant therapy in SJS/TEN is retrospective. Recent, open-label, prospective non-comparative studies investigating the use of cyclosporine, and a randomized, unblinded clinical trial comparing etanercept with corticosteroids have demonstrated a possible benefit of these treatments in SJS/TEN.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(1):92–6.

Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, Daoud YJ, Ahmed AR, Foster CS. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(4):419–36; quiz 36–8, 56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61112-X.

Goodman H. Nikolsky sign; page from notable contributors to the knowledge of dermatology. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;68(3):334–5.

Harr T, French LE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-5-39.

• Jun I, Rim JH, Kim MK, Yoon KC, Joo CK, Kinoshita S, et al. Association of human antigen class I genes with cold medicine-related Stevens-Johnson syndrome with severe ocular complications in a Korean population. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(4):573–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313263This multicentre case-control study found significant difference in gene frequency for HLA-A*02:06 (37% vs 20%) and HLA-C*03:04 (15% vs 5.4%) in patients with SJS/TEN patients compared with age, sex matched controls, respectively.

Nicoletti P, Barrett S, McEvoy L, Daly AK, Aithal G, Lucena MI, et al. Shared genetic risk factors across carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1493.

Correia O, Delgado L, Ramos JP, Resende C, Torrinha JA. Cutaneous T-cell recruitment in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Further evidence of CD8+ lymphocyte involvement. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(4):466–8.

Paul C, Wolkenstein P, Adle H, Wechsler J, Garchon HJ, Revuz J, et al. Apoptosis as a mechanism of keratinocyte death in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(4):710–4.

Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R, Schneider P, Holler N, Salomon D, et al. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science (New York, NY). 1998;282(5388):490–3. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5388.490.

Nassif A, Bensussan A, Boumsell L, Deniaud A, Moslehi H, Wolkenstein P, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: effector cells are drug-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(5):1209–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2004.07.047.

Wei CY, Chung WH, Huang HW, Chen YT, Hung SI. Direct interaction between HLA-B and carbamazepine activates T cells in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1562–9 e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.990.

Genin E, Schumacher M, Roujeau JC, Naldi L, Liss Y, Kazma R, et al. Genome-wide association study of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal Necrolysis in Europe. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-6-52.

Borchers AT, Lee JL, Naguwa SM, Cheema GS, Gershwin ME. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(8):598–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2008.06.004.

Rzany B, Mockenhaupt M, Baur S, Schroder W, Stocker U, Mueller J, et al. Epidemiology of erythema exsudativum multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Germany (1990-1992): structure and results of a population-based registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(7):769–73.

Strom BL, Carson JL, Halpern AC, Schinnar R, Snyder ES, Shaw M, et al. A population-based study of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Incidence and antecedent drug exposures. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127(6):831–8.

Chan HL, Stern RS, Arndt KA, Langlois J, Jick SS, Jick H, et al. The incidence of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis. A population-based study with particular reference to reactions caused by drugs among outpatients. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126(1):43–7.

Roujeau JC, Chosidow O, Saiag P, Guillaume JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6 Pt 1):1039–58.

Schopf E, Stuhmer A, Rzany B, Victor N, Zentgraf R, Kapp JF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. An epidemiologic study from West Germany. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127(6):839–42.

• Frey N, Jossi J, Bodmer M, Bircher A, Jick SS, Meier CR, et al. The epidemiology of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in the UK. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(6):1240–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.01.031This large obersvational study of over 500 patients from the UK calculated an incidence of 5.76 SJS/TEN cases per million person-years between 1995 and 2013. They found black and Aisian patients to be at 2-fold risk. They observed increased odds for patients with epilepsy and gout who were taking a antiepileptics or allopurinol. They also observed assosciations with pre-existing depresion, lupus erythematosus, pneumonia, kidney disease, and cancer.

• Yang MS, Lee JY, Kim J, Kim GW, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Incidence of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a nationwide population-based study using national health insurance database in Korea. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165933. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165933This Korean population-based study obtained records of 938 SJS cases and 229 TEN cases between 2009 and 2013. They observed an incidence of 3.96–5.03 and 0.94 to 1.45 in SJS and TEN, respectively. Incidence was relatively stable for each year of the study. In hosptial mortality was 5.7% for the patients with SJS and 15.1% for the patients with TEN.

Naegele D, Sekula P, Paulmann M, Mockenhaupt M. Incidence of Stevens-Johnson syndrom/toxic epidermal necrolysis: results of 10 years from the German registry. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:3.

• Hsu DY, Brieva J, Silverberg NB, Silverberg JI. Morbidity and mortality of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in United States adults. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(7):1387–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.023This US cohort consisted of 2591 patients with SJS, 502 with SJS/TEN overlap, and 564 with TEN from a nationwide inpatient sample between 2009 and 2012. The estimated incidences were 9.2, 1.6, and 1.9 per million adults per year, respectively. There was increased odd for Asian (OR 3.27) and black (OR 2.01) patients. Mean adjusted mortality was 4.8% for SJS, 19.4% for overlap, and 14.8% for TEN.

• Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, Stephen S, Aleshin M, Agarwal A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(11):2315–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.04.027This multi-center retrospective study of 377 patients with SJS/TEN positviely identified a medications as the cause for 89.7% of patients, most often trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (26.3%). Most patients were managed in the intensive care or burn unit and most received pharmacologic therapy compared with supportive care alone. The in-hospital mortality was lower (54 deaths) than predicted by SCORTEN (78 deaths). Standardized mortality ratio (0.52) was lowest for patients receiving combination IVIg and corticosteroids.

Huang YC, Li YC, Chen TJ. The efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(2):424–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10965.x.

Sekula P, Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, Naldi L, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Halevy S, et al. Comprehensive survival analysis of a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(5):1197–204. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.510.

Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, Roujeau JC, Revuz J. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(2):272–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700068.

• Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, Mostaghimi A, Cardones AR, Chen JK, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality among patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal ncrolysis—ABCD-10Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality of patients with SJS/TENDevelopment and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality of patients with SJS/TEN. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(4):448–54. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5605This study utilized a multicenter cohort of 370 patients with SJS/TEN to derive a new risk prediction model called the ABCD-10. The new model give one point for age over 50 years, 10% or greater body surface area of epidermal detachment, and serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L. Two points are given to patients with active cancer status. Three points are given for a history of dialysis within one year of admission. The ABCD-10 model showed good discrimination (AUC 0.816,p= 0.03) but was not significantly different from the SCORTEN (AUC 0.827).

Scott-Lang V, Tidman M, McKay D. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a child successfully treated with infliximab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(4):532–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12029.

Aires DJ, Fraga G, Korentager R, Richie CP, Aggarwal S, Wick J, et al. Early treatment with nonsucrose intravenous immunoglobulin in a burn unit reduces toxic epidermal necrolysis mortality. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(6):679–84.

• Nizamoglu M, Ward JA, Frew Q, Gerrish H, Martin N, Shaw A, et al. Improving mortality outcomes of Stevens Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a regional burns centre experience. Burns. 2018;44(3):603–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2017.09.015This retrospective review of 42 patients with TEN or SJS/TEN overlap who were managed in a burn service over a total of 12 years had a total of 4 deaths compared with 16 predicted by SCORTEN. Investigators concluded that the management in a burn service with aggressive wound care involving debridement and synthetic and biologic dressing seems to have a mortality benefit.

Zhang AJ, Nygaard RM, Endorf FW, Hylwa SA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: retrospective review of 10-year experience. Int J Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.14409.

• Creamer D, Walsh SA, Dziewulski P, Exton LS, Lee HY, Dart JK, et al. U.K. guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults 2016. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(6):1194–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14530These 2016 guidelines were established to help providers in the management of SJS/TEN. These evidence-based recommendations are graded based on strength of the supporting research and include management of initial presentation, supportive care, and adjuvant therapy.

• McPherson T, Exton LS, Biswas S, Creamer D, Dziewulski P, Newell L, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17841These 2018 guidelines from the British Association of Dermatologists provide up to date, evidence-based recommendations on the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN in children (0–12 years) and young people (13–17 years). Their recommendations focus primarily on the acute phase of the disease. They appraise all relevant literature, focusing on recent developments and address practical clinical questions as well as areas of uncertainty.

• Gupta LK, Martin AM, Agarwal N, D’Souza P, Das S, Kumar R, et al. Guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: an Indian perspective. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(6):603–25. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.191134The Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists (IADVL) prepared these guidelines on management of SJS/TEN. Their recommendations include prompt withdrawal of the culprint drug, meticulous supportive care, and judicious and early initiation of moderate to high doses of oral or parenteral corticosteroids. Cyclosporine use was also recommended either alone or in combination with corticosteroids. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of these patients is recommended as helpful.

• Schneider JA, Cohen PR. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a concise review with a comprehensive summary of therapeutic interventions emphasizing supportive measures. Adv Ther. 2017;34(6):1235–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0530-yThis review serves to concisely and comprehensively summarize therapeutic interventions for SJS/TEN. They emphasize supportive care as the mainstay for treatment of these patients. They recommend a case-by-case evaluation of patients for adjuvant therapies, as a standardized management approach for these medications is not yet clear based on current data.

• Garcia-Doval I, LeCleach L, Bocquet H, Otero XL, Roujeau JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(3):323–7 This study is on a consecutive sample of 113 patients with SJS/TEN. After adjusting for confounding variables, the study showed that prompt withdrawal of causative drugs was associated with decreased mortality. The authors’ recommendation is thus to promptly withdraw causative drugs, especially when blisters or erosions appear.

• Yamane Y, Matsukura S, Watanabe Y, Yamaguchi Y, Nakamura K, Kambara T, et al. Retrospective analysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in 87 Japanese patients--treatment and outcome. Allergol Int. 2016;65(1):74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2015.09.001This is a retrospective analysis of 52 cases of SJS and 35 cases of TEN, evaluating treatment and outcome. The study showed that treatment with steroid pulse therapy in combination with plasmapheresis and/or immunoglobulin therapy seems to have contributed to prognostic improvement in SJS/TEN.

• Castillo B, Vera N, Ortega-Loayza AG, Seminario-Vidal L. Wound care for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(4):764–7 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.032This article is a literature review of SJS/TEN wound care, with the aim to assess the effets of dressing used in wound care and present evidence -based recommendations to assist clinicians in the best approach to wound care. The authors concluded that modern dressings should be part of standard therapy because of less frequent changes and improved patient comfort.

• Rogers AD, Blackport E, Cartotto R. The use of Biobrane((R)) for wound coverage in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Burns. 2017;43(7):1464–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2017.03.016This is a retrospective review of 42 patients with SJS/TEN, where Biobrane was applied in 24 cases. The conclusion was that Biobrane was applied to SJS/TEN patients with more extensive epidermal detachment, but had no significant complications and generallly facilitated epidermal healing at a rate not significantly different from dressing-only treated subjects.

• Spies M, Sanford AP, Aili Low JF, Wolf SE, Herndon DN. Treatment of extensive toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(5):1162–8 This is case series studying treatment of SJS/TEN in 15 patients. TEN is a rare disease in patients, and the study found that it was successfully managed in a burn center environment, using early debridement and wound coverage with allograft skin as a biological dressing. The management was unchanged in the past 2 decades, indicating an additional need for information and education about the disease.

• Lee HY. Wound management strategies in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: an unmet need. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(4):e87–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1258This brief letter describes the use of conservative versus surgical approaches for wound care in SJS/TEN. It describes side effects of surgical approaches, including postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dorafshar AH, Dickie SR, Cohn AB, Aycock JK, O’Connor A, Tung A, et al. Antishear therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis: an alternative treatment approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(1):154–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181773d5d.

Mayes T, Gottschlich M, Khoury J, Warner P, Kagan R. Energy requirements of pediatric patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23(5):547–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533608323434.

• Koh HK, Chai ZT, Tay HW, Fook-Chong S, Choo KJ, Oh CC, et al. Risk factors and diagnostic markers of bacteraemia in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a cohort study of 176 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.096This single-center retrospective cohort study of 176 patients with SJS/TEN found that 29.5% of patients had bacteremia, which was associated with increased mortality, lonter hosptial stay and higher ICU admission. Isolated included Acinetobacter baumannii (27.7%) and Staphylococcus aureus (21.4%). Other clinical factors that were predictive of bacteraemia include: hemoglobin less than or equal to 10g/dL, existing cardiovascular disease, and body surface area greater than 9%. Hypothermia and elevated pro-calcitonin were predictive of blood culture positivity.

Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Spence RJ, Peck MD, Jeng JC, et al. A multicenter review of toxic epidermal necrolysis treated in U.S. burn centers at the end of the twentieth century. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23(2):87–96.

Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(2):187 e1–16; quiz 203-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.002.

Meneux E, Paniel BJ, Pouget F, Revuz J, Roujeau JC, Wolkenstein P. Vulvovaginal sequelae in toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Reprod Med. 1997;42(3):153–6.

Kaser DJ, Reichman DE, Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4(2):81–5.

Kaser DJ, Reichman DE, Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4(2):81–5.

Chang YS, Huang FC, Tseng SH, Hsu CK, Ho CL, Sheu HM. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: acute ocular manifestations, causes, and management. Cornea. 2007;26(2):123–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e31802eb264.

Yip LW, Thong BY, Lim J, Tan AW, Wong HB, Handa S, et al. Ocular manifestations and complications of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an Asian series*. Allergy. 2007;62(5):527–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01295.x.

Morales ME, Purdue GF, Verity SM, Arnoldo BD, Blomquist PH. Ophthalmic manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis and relation to SCORTEN. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(4):505–10.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2010.04.026.

Gueudry J, Roujeau J-C, Binaghi M, Soubrane G, Muraine M. Risk factors for the development of ocular complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145(2):157–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2009.540.

Van Zyl L, Carrara H, Lecuona K. Prevalence of chronic ocular complications in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21(4):332–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.142272.

Sotozono C, Ueta M, Nakatani E, Kitami A, Watanabe H, Sueki H, et al. Predictive factors associated with acute ocular involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(2):228–37.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.002.

Sharma N, Thenarasun SA, Kaur M, Pushker N, Khanna N, Agarwal T, et al. Adjuvant role of amniotic membrane transplantation in acute ocular Stevens–Johnson syndrome: a randomized control trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(3):484–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.027.

Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(5):908–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.046.

Kohanim S, Palioura S, Saeed HN, Akpek EK, Amescua G, Basu S, et al. Acute and chronic ophthalmic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis – a comprehensive review and guide to therapy. II Ophthalmic Disease. Ocular Surf. 2016;14(2):168–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2016.02.001.

Dodiuk-Gad RP, Olteanu C, Feinstein A, Hashimoto R, Alhusayen R, Whyte-Croasdaile S, et al. Major psychological complications and decreased health-related quality of life among survivors of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(2):422–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14799.

Patmanidis K, Sidiras A, Dolianitis K, Simelidis D, Solomonidis C, Gaitanis G, et al. Combination of infliximab and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for toxic epidermal necrolysis: successful treatment of an elderly patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2012;2012:915314. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/915314.

Fischer M, Fiedler E, Marsch WC, Wohlrab J. Antitumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies (infliximab) in the treatment of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(4):707–9.

Hunger RE, Hunziker T, Buettiker U, Braathen LR, Yawalkar N. Rapid resolution of toxic epidermal necrolysis with anti-TNF-α treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(4):923–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.029.

Hirahara K, Kano Y, Sato Y, Horie C, Okazaki A, Ishida T, et al. Methylprednisolone pulse therapy for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical evaluation and analysis of biomarkers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(3):496–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2013.04.007.

• Zimmermann S, Sekula P, Venhoff M, Motschall E, Knaus J, Schumacher M, et al. Systemic immunomodulating therapies for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(6):514–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5668This Ssystemic review of 96 studies and 3248 patients with SJS/TEN provides a comprehensive review of systemic immunomodulating therapies compared to with supportive care. Mortality benefits expressed as OR were found for cyclosporine and glucocoriticoids in unstratified models.

Aoki Y, Kao PN. Cyclosporin A-sensitive calcium signaling represses NFkappaB activation in human bronchial epithelial cells and enhances NFkappaB activation in Jurkat T-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234(2):424–31. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1997.6658.

Roujeau JC, Bastuji-Garin S. Systematic review of treatments for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using the SCORTEN score as a tool for evaluating mortality. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(3):87–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098611404094.

Paradisi A, Abeni D, Bergamo F, Ricci F, Didona D, Didona B. Etanercept therapy for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):278–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.044.

• Wang CW, Yang LY, Chen CB, Ho HC, Hung SI, Yang CH, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of TNF-alpha antagonist in CTL-mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(3):985–96. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI93349This randomized, controlled trial of 96 patients with SJS/TEN found that Eetanercept decreased the SCORTEN-predicted mortality rate compared to with corticosteroids. Investigators also observed a significantly reduced skin-healing time in the moderate-to-severely affected patients (p = 0.010). Enteracept groups had reduced granulysin in blister fluids and plasma and an increased Treg cell population (p = 0.002) - —providing insights on the potential mechanism-of-action.

Shah R, Chen ST, Kroshinsky D. Use of cyclosporine for the treatment of Steven Johnson syndrome/ toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.063.

• Han F, Zhang J, Guo Q, Feng Y, Gao Y, Guo L, et al. Successful treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis using plasmapheresis: a prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2017;42:65–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.07.002This prospective observational study evaulated the response of 28 patients to plasmapheresis tehrapy after admission for SJS/TEN. Severity of disease and efficacy of treatments were evaluated by the severity-of-illness score for TEN. Results indicated that plasmapheresis may be superior to conventional therapy, and that plasmapheresis alone may be more beneficial than combination therapies.

Morici MV, Galen WK, Shetty AK, Lebouef RP, Gouri TP, Cowan GS, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for children with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(10):2494–7.

Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Brochard L, Ortonne N, Maitre B, Revuz J, et al. Open trial of ciclosporin treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(4):847–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09863.x.

Furubacke A, Berlin G, Anderson C, Sjoberg F. Lack of significant treatment effect of plasma exchange in the treatment of drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis? Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(11):1307–10.

Narita YM, Hirahara K, Mizukawa Y, Kano Y, Shiohara T. Efficacy of plasmapheresis for the treatment of severe toxic epidermal necrolysis: is cytokine expression analysis useful in predicting its therapeutic efficacy? J Dermatol. 2011;38(3):236–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01154.x.

Kostal M, Blaha M, Lanska M, Kostalova M, Blaha V, Stepanova E, et al. Beneficial effect of plasma exchange in the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis: a series of four cases. J Clin Apher. 2012;27(4):215–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/jca.21213.

Barron SJ, Del Vecchio MT, Aronoff SC. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a meta-analysis with meta-regression of observational studies. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(1):108–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.12423.

Del Pozzo-Magana BR, Lazo-Langner A, Carleton B, Castro-Pastrana LI, Rieder MJ. A systematic review of treatment of drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2011;18:e121–33.

Michaels B. The role of systemic corticosteroid therapy in erythema multiforme major and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a review of past and current opinions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2(3):51–5.

Schneck J, Fagot JP, Sekula P, Sassolas B, Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M. Effects of treatments on the mortality of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective study on patients included in the prospective EuroSCAR Study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.039.

• Ng QX, De Deyn M, Venkatanarayanan N, Ho CYX, Yeo WS. A meta-analysis of cyclosporine treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:135–42. https://doi.org/10.2147/jir.S160964This meta-analysis of 9 studies demonstrated significant mortality reduction with a standardized mortality ratio of 0.320 (p = 0.002). Cyclosporine was well tolerated with few adverse efects. There was observed publication bias (p = 0.0467).

• Chen Y-T, Hsu C-Y, Chien Y-N, Lee W-R, Huang Y-C. Efficacy of cyclosporine for the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: systemic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Sin. 2017;35(3):131–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsi.2017.04.004This systemic review of 7 studies compared mortality rates for patients receiving cyclosporine vs those receiving IVIg (4 studies), corticosteroids (1 study), combination therapy consisting of steroids and cyclophosphamiden 1 study), and supportive therapy (2 studies). Cyclosporine had significantly higher mortality benefit compared to with all other groups.

Kirchhof MG, Miliszewski MA, Sikora S, Papp A, Dutz JP. Retrospective review of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treatment comparing intravenous immunoglobulin with cyclosporine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(5):941–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.016.

• Gonzalez-Herrada C, Rodriguez-Martin S, Cachafeiro L, Lerma V, Gonzalez O, Lorente JA, et al. Cyclosporine use in epidermal necrolysis is associated with an important mortality reduction: evidence from three different approaches. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(10):2092–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.05.022This retrospective study compared the outcomes at two different burn units in Madrid over the period from 2001 to 2015. On unit utilized cyclosporine while the tother used non-cyclosporine regimens. Investigators also observed outcomes for a case series of 49 patients who were treated in other regions of Madrid and an additional five case series. Investigators found that cyclosporine consistently reduced mortality.

Reese D, Henning JS, Rockers K, Ladd D, Gilson R. Cyclosporine for SJS/TEN: a case series and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;87(1):24–9.

• St John J, Ratushny V, Liu KJ, Bach DQ, Badri O, Gracey LE, et al. Successful use of cyclosporin A for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in three children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(5):540–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.13236This case series explored the efficacy of Ccyclosporine A in the treatment of SJS/TEN in three pediatric patients. Treatment with Ccyclosporine A for these patients was successful, with an average of 2.2 days to cessation of disease (range 1.5–-3 days) and 13 days to re-epithelialization (range 10–-15 days). Average hospital stay was 11.7 days (range 4–-19 days).

• Poizeau F, Gaudin O, Le Cleach L, Duong TA, Hua C, Hotz C, et al. Cyclosporine for epidermal necrolysis: absence of beneficial effect in a retrospective cohort of 174 patients-exposed/unexposed and propensity score-matched analyses. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(6):1293–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.12.034This retrospective review of 174 patients with SJS/TEN from 2005–-2016 found no statistically significant beneficial effect on mortality, duration of progression and re-epithelialization status at day 5 or 10 for non-mucosal and mucosal skin, respectively.

Singh GK, Chatterjee M, Verma R. Cyclosporine in Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis and retrospective comparison with systemic corticosteroid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(5):686–92. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.116738.

• Curtis JA, Christensen LC, Paine AR, Collins Brummer G, Summers EM, Cochran AL, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis treatments: an Internet survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(2):379–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.033The investigators of this study surveyed 290 providers (of 1927 providers sent the survey link) who had treated a patient with SJS/TEN in the past year. The survey showed that the majority of providers don’t use systemic steroids for any classification of SJS/TEN. Most preferred IVIG in SJS/TEN overlap or TEN, but some did not use IVIG in SJS cases. Cyclosporine was the most frequently used alternative therapy. Most providers did not debride the skin and preferred petrolatum-impregnated gauze and nonadherent dressings with nanocrystalline silver.

Trent J, Halem M, French LE, Kerdel F. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and intravenous immunoglobulin: a review. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25(2):91–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sder.2006.04.004.

Prins C, Vittorio C, Padilla RS, Hunziker T, Itin P, Forster J, et al. Effect of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a retrospective, multicenter study. Dermatology. 2003;207(1):96–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000070957.

Metry DW, Jung P, Levy ML. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: seven cases and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1430–6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.6.1430.

Jagadeesan S, Sobhanakumari K, Sadanandan SM, Ravindran S, Divakaran MV, Skaria L, et al. Low dose intravenous immunoglobulins and steroids in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a prospective comparative open-labelled study of 36 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(4):506–11. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.113080.

Zhu QY, Ma L, Luo XQ, Huang HY. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: performance of SCORTEN and the score-based comparison of the efficacy of corticosteroid therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin combined therapy in China. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(6):e295–308. https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e318254d2ec.

• Ye LP, Zhang C, Zhu QX. The effect of intravenous immunoglobulin combined with corticosteroid on the progression of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0167120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167120This meta-analysis of 26 studies including 628 patients evaluated the efficacy of IVIG combined with corticosteroids on the progression of SJS/TEN. They found that this combination therapy could reduce recovery time, especially in Asian patients. However, its impact on reducing mortality was not significant.

Zarate-Correa LC, Carrillo-Gomez DC, Ramirez-Escobar AF, Serrano-Reyes C. Toxic epidermal necrolysis successfully treated with infliximab. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23(1):61–3.

Wolkenstein P, Latarjet J, Roujeau JC, Duguet C, Boudeau S, Vaillant L, et al. Randomised comparison of thalidomide versus placebo in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1998;352(9140):1586–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02197-7.

Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, Roujeau JC, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115(2):149–53. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x.

• Morita K, Matsui H, Michihata N, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Association of early systemic corticosteroid therapy with mortality in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective cohort study using a nationwide claims database. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;30:30 This large retrospective cohort study of 1846 patients evaluated the association of early systemic corticosteroid therapy with mortality in patients with SJS/TEN. Their results indicated that eary systemic corticosteroid therapy was not associated with lower in-hospital mortality.

• Liu W, Nie X, Zhang L. A retrospective analysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis treated with corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(12):1408–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13379This study retrospective analysis of 70 patients with SJS/TEN evaluated a response to treatment with corticosteroids. The study supports the use of corticosteroids in SJS/TEN as it was associated with lower mortality rate and serum albumin levels. Investigators conclude that corticosteroids should be administered in accordance with disease severity, age, underlying diseaes, serum albumin level, and concurrent antimicrobial therapy.

Roongpisuthipong W, Prompongsa S, Klangjareonchai T. Retrospective analysis of corticosteroid treatment in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and/or toxic epidermal necrolysis over a period of 10 years in Vajira Hospital, Navamindradhiraj University, Bangkok. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:237821. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/237821.

• Lee HY, Fook-Chong S, Koh HY, Thirumoorthy T, Pang SM. Cyclosporine treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: retrospective analysis of a cohort treated in a specialized referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(1):106–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.048This retrospective analysis of 44 patients sought to evaluate the impact of cyclosporine on hospital mortality in patients with SJS/TEN. 24 patients received cyclosporine and 20 were treated supportively. SCORTEN predicted 7.5 deaths in the cyclosporine group, and 3 were observed. SCORTEN predicted 5.9 deaths in the supportive group, and 6 were observed. Thus, the standardized mortality ratio of SJS/TEN treated with cyclosporine was 0.42. They concluded that the use of cyclosporine may improve mortality in SJS/TEN.

• Lee HY, Lim YL, Thirumoorthy T, Pang SM. The role of intravenous immunoglobulin in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective analysis of 64 patients managed in a specialized centre. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(6):1304–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12607This retrospective cohort study of 42 patients sought to investigate the association between type of immune modulatory treatment administered and prognosis of patient. They found apparent reduced mortality in patients treated with combination IVIG and corticosteroid therapy.

Chan L, Cook DK. A 10-year retrospective cohort study of the management of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a New South Wales state referral hospital from 2006 to 2016. Int J Dermatol. 2019;25:25.

Chen J, Wang B, Zeng Y, Xu H. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins in the treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Chinese patients: a retrospective study of 82 cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20(6):743–7. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2010.1077.

Paquet P, Jennes S, Rousseau AF, Libon F, Delvenne P, Piérard GE. Effect of N-acetylcysteine combined with infliximab on toxic epidermal necrolysis. A proof-of-concept study. Burns. 2014;40(8):1707–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2014.01.027.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Hospital-Based Dermatology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coias, J.L., Abbas, L.F. & Cardones, A.R. Management of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: a Review and Update. Curr Derm Rep 8, 219–233 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-019-00275-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-019-00275-0